This is the shortest chapter in the entire book of Job, so it would be easy to just breeze right by it. But it’s the one I really, really struggle with the most. What is so wrong about Bildad’s argument? Isn’t he right? All people sin. No one is righteous before God. It says that. The Bible says that.

How can a mortal be innocent before God?

Can anyone born of a woman be pure? (Job 25:4)

For everyone has sinned; we all fall short of God’s glorious standard. (Romans 3:23)

God looks down from heaven

on the entire human race;

he looks to see if anyone is truly wise,

if anyone seeks God.

But no, all have turned away;

all have become corrupt.

No one does good,

not a single one! (Psalm 53:2-3)

I was praying about this chapter because I do not know what to make of it. Job’s friends have now gone through all the common arguments about why suffering exists: 1) punishment for sufferer’s sin (they really harped on this one), 2) punishment for someone else’s sin (those naughty children), and 3) generalized sin leads to generalized suffering. Since they cannot find any other reason for Job’s suffering, this is where they ended up. No one is perfectly righteous, Bildad says. Because no one can be perfect, you must have sinned, and that is why you are suffering.

I have heard people make all of these arguments. When I was diagnosed with a painful condition early in our marriage, I wondered if it was because of something I had done. I wracked my brain looking for something to blame, for some unrepented sin that made this happen. My husband used to constantly blame the struggles in our life on foolish choices he made when he was young, and he would mentally thrash himself again and again for those choices. When my oldest daughter was born with a heart defect, we were told it was because we had sinned. “Which man sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born like this?” That attitude still exists, even in the modern church that has the next words of Jesus: “Neither this man nor his parents sinned.”

Let’s look, though, at the origin of this belief, this attitude toward suffering. There’s a good example of sin leading to suffering in Joshua 6 after the Israelites destroyed Jericho. The story is iconic. The people were given the strangest orders to march around the city without making a sound, and then, when they had marched around the directed number of times, they were to shout with all their might. We know this story because the walls literally crumbled in front of them. We like this part of the story.

But it does not end there, does it? The people are given the command to put to death every person and animal in Jericho, and they are to destroy or consecrate to the Lord all of the spoils of battle; the gold and the silver and the fine clothing. They were given precise instructions. Keep none of it, the Lord said. But Achan did not listen.

The next battle should have been an easy one. The spies came back full of confidence, saying the people were few and it would only take a couple thousand men to destroy them. They sent three thousand just to be on the safe side. They did not even bother to ask the Lord about it. No point for such an obvious and easy battle.

They were “soundly defeated.” (Joshua 7:4) Thirty-six men died. That might not sound like a lot for a battle. But every man is one too many, and it was more than they had ever lost before. They were so surprised, so horrified, that it says “their courage melted away.” (Joshua 7:5)

Then they asked the Lord why that had happened, and then he exposed Achan’s disobedience. Thirty-six men died because one man wanted a pretty robe and some silver and gold. Sin = punishment.

Now, is it more complicated than that? Of course. There was also a certain arrogance that had befallen God’s people, a certain entitlement to his power. If they had asked before they went, how differently would the ending have been?

Also, God did not raise his hand to strike those thirty-six men himself. He simply let Israel find out how much of their victory came from his strength and how much of it came from their own. He let them try it without him. They found out right quick and in a hurry that God’s way works and theirs does not.

But the fact remains that God traced the root of their failure back to disobedience, and rather than learning from the Israelites to ask God before making assumptions, what most people take away from this moment is that suffering comes from sin.

This is not a solitary moment in Israel’s history; over and over again they disobey God, and over and over again he lets them find out what it’s like to live without him. It turns out they’re a lot weaker than they think. It turns out most of what they thought was their success was actually God’s. It turns out a lot of us try to claim God’s victories for ourselves. When we do, it obscures others’ views of God’s character. When we do, people learn to falsely worship us instead of truly worshipping God. It was never the Israelites the nations should have feared, but their God.

But instead of learning to fear and worship God, instead of learning to consult him first and do what he says, people have instead tried to figure out how we can control the outcome.

So what is so wrong about what Job’s three friends are saying? Well. I have not heard one of them say, “I asked God, and he said…” They’re all still trying to figure out the right answer by themselves. None of them have actually talked to God. When Job suggests it, they actively discourage him. They’re like the Israelites attacking Ai without asking – no need to bother God for something we can do ourselves.

But they can’t figure it out, can they. That’s because this is one of those, “Neither this man nor his parents sinned,” kind of moments that Jesus used to knock that faulty logic off its stand. But the disciples did something Job’s three friends did not; they asked. So Job’s three friends don’t know that sometimes God has different reasons than the ones we understand.

All their usual explanations have failed them. And when all other explanations fail, people say, “We live in a fallen world.” I always thought they meant we are all sinful, and we all deserve it.

To some extent, that’s true. It’s forgiveness, mercy, and grace most of us mortals do not deserve. An eye for an eye is fair – equal and balanced – but it is not good, is it? No, when the first wrong, the first bad thing, happened, it could only be equaled, could only be balanced by another bad thing. It may be fair, but in the end sometimes what we see as fair is only doubly bad. It may be justice, but it is not perfect justice – that is to say, it is not mercy, but sacrifice.

I would say perfect justice begins with a kindness, not a cruelty. I would say it equals and balances that kindness with another kindness. I am kind to you, and then you are equally kind to me. Balance. Justice. The perpetuation of kindness and love. That is the kind of justice, I think, that God prefers. That is what makes what happened to Job so objectionable, isn’t it? He was kind and he was generous and he gave with an open heart, and others were cruel and others were selfish and others took from him what was his. The earth itself stole from him with the natural disasters that burned up his business and killed his children. It was not equal, and it was not balanced.

What is wrong with Job’s three friends’ arguments is that they are trying to prove that what happened to Job was equal and was balanced. They were trying to prove that it was fair. But anyone with eyes can tell you life is not fair. Something is unequal here. Something is unbalanced. Something needs fixing.

So what was wrong with Bildad’s argument is that he is trying to use something that is true – God is glorious, and we will never measure up to him – to support a fallacy, that what happened to Job was just.

It is true that no one is righteous next to God. Who could be? By sheer size alone, God is stronger. By sheer size alone, God has the resources to be more generous. By sheer size alone, God’s mind can be more right. By sheer size alone, God’s heart can hold more love. We can be nothing to him. We can never equal him. We can never balance him.

But. Does that mean it is right for us to be punished for not measuring up to him?

This gets into slippery territory.

Someone might argue, “If my falsehood enhances God’s truthfulness and so increases his glory, why am I still condemned as a sinner?” (Romans 3:7, NIV)

But as always, God is right. What good is it to argue about whether or not we should be held to God’s potential as a standard for goodness? We don’t measure up to our own potential, let alone his. That is enough for us to be condemned.

But the question in Job is not about whether or not he deserves eternal condemnation for not being able to counterbalance the goodness of God. That will be judged at the end of the age, and it will depend on far more than what he has done. He will need more than himself for that measurement. No, the question is whether or not he deserves the intense earthly suffering – beyond what most have to endure – that has befallen him here, in his earthly life. We can see, even in our humanity, that some people suffer more than others. The question is whether or not those people deserve to suffer more than the rest of us. Whether or not God knows something about these people that we do not, whether or not their suffering is evidence of some great, hidden (or not so hidden) sin.

Bildad’s argument falls profoundly flat in the face of that question, regardless of whether or not what he says is true. Sure, all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. But does that explain why some suffer more than others? No. By Bildad’s argument – and by the Bible’s truth – we are all equal under the rule of sin. “Don’t be ridiculous, Job,” he says, “everybody has sinned, so you must have, too. That’s why all this bad stuff is happening to you.”

Frankly, then, if Bildad’s argument was valid, unequal suffering for equal sin is still wrong. Even if Bildad’s argument was correct, we’re still left wondering why this happened to Job, but not everyone else.

He cannot refute what Job has said – that sometimes people cheat and get away with it. Sometimes people do terrible things and go unpunished. And sometimes people do great things, kind things, and are punished despite, or even for being good.

Again, this is an integral truth that must be accepted for the basic tenets of Christianity to be believed. If we do not believe the innocent suffer, then who is Christ? But he took our sins upon himself, some will argue. So he was not considered innocent anymore. He was innocent, I will tell you, or else he could not have substituted himself for us. It was the one qualification he had to meet to be our perfect sacrifice.

Martyrs. Saints. Kidnapped aide workers. Victims of the Holocaust. Abused children. All the way back to Abel, second generation human, who was murdered by his brother for bringing a better sacrifice to God.

Our theology must must must allow the innocent to suffer, or it is empty. It ignores what is real. It. is. fake.

The fact of the matter is what happened to Job was wrong. It was unequal and it was unbalanced. Something in the universal justice system is broken and has been broken since the fall of man, since God was generous and kind and gave mankind something good and man was selfish and cruel and stole something more. We broke the balance. By trying to justify, or make it somehow right, that innocent people suffer, we undercut the basic truth that something is flat out wrong here, and it needs to be fixed.

That is what it means to live in a fallen world. It is unequal. It is unbalanced. Bad things are done to people who are doing good. Like Job.

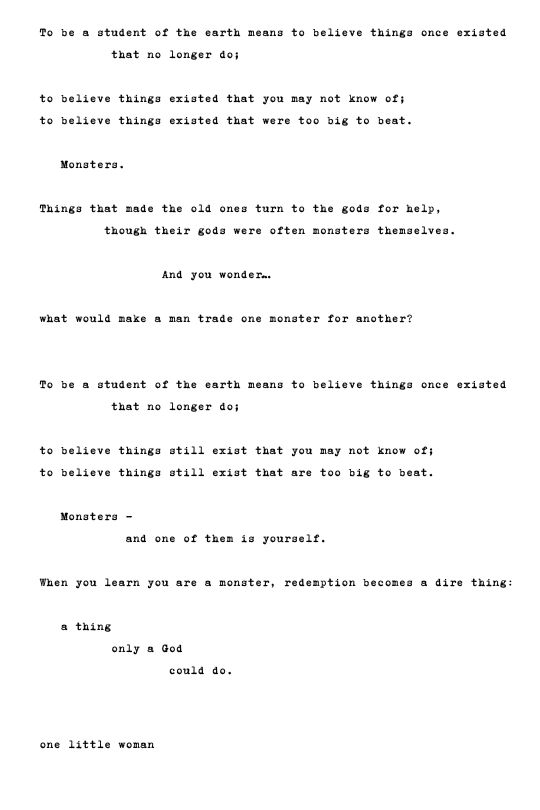

But who can fix it? Job cries out throughout the beginning of this book. Humans cannot be good enough, strong enough, loving enough to fix this broken world! All our love and all our goodness cannot balance the scales.

Yes, exactly. That’s the point.

This is a kind of broken only God can fix.

Job can see the need. He has declared that it will be met one day. But he cannot see how. He cannot see who. He can only see that the system is broken, and it needs fixing.

Come, Lord Jesus.